Last weekend, I took a train upstate to Storm King Art Center and the nearby Schunemuck State Park. It was a solitary trip by design, and it gave me a lot of time and space — about 8 hours and 23 miles — with nothing but the vibrant autumn trees, my music, and chilly air to keep me company. Well… rather, it let me spend some quality time reflecting upon my Brain and Mind.

After these 7 tumultuous weeks, a trip like that it was necessary. Our neurology/psychiatry unit Brain and Mind Behavior, henceforth known as BAM, has been difficult, intriguing, engaging, and terrifying. To me, it is the least well understood and most emotionally charged branch of medicine, and thinking about it offers plenty of valuable insight into everyone’s brains, no matter how healthy we think they are.

Terrifying patients

Technically speaking, this was not my first time up north. Every week, my classmates and I get shuttled up to NYP Westchester — a renowned dedicated psych hospital — where we learn how to conduct psychiatric interviews with real patients with real psychiatric illnesses. The first patient I met was a young man with a long history of schizophrenia and paranoid delusional disorder. He “acts out” by committing acts of vandalism and harm, but it happens so often that his entire community knows to not to call the police but instead call the hospital. At Westchester, staff recognize him as a “regular,” and he feels safe because he trusts that they’ll help stabilize him with medication.

That comfort a remarkable feat, considering that he believes with conviction that the woman who lives in the house he calls home is NOT his mother. Trust him, he’s had genetic testing. He acknowledges that he can see, hear, and feel people telling him to do bad things or coming to hurt him, but that doesn’t strike him as odd. He tells us stories of how he was drowned, shot in the head, born in two places, and has finished law school. He knows his diagnosis, is aware of his many hospital visits, and knows that his beliefs are self-contradictory.

Schizophrenia is terrifying because it compromises you. Your mind. Your self. You have nothing to connect you to the world other than your perception (see VSauce on consciousness), and schizophrenia is a disorder that comes and destroys precisely that. He and the other schizophrenic patients I’ve met lack “insight,” meaning they don’t quite realize what it means for them to be sick. We as observers can perceive that his perception of reality is warped, but when he “acts out” or “breaks down,” he’s looking right back us and thinking that he sees it straight and it’s us that’s warping things.

Well, who’s to say we’re right and he’s wrong? How do even convince him otherwise?

Autumn leaves

With lessons like that, it’s no wonder I felt compelled to get out of town a little bit. Enjoy the simple things in life, like the glorious changing leaves of the northeast. I used to say that according to my photos winter is my statistically favorite season, but now I realize it’s because the photogenic moment of autumn — autumn foliage — happens precisely once a year (unlike snowstorms…). So when my classmates brought back photos from upstate showing lots of turning trees, I kinda panicked about missing it and rushed up there as soon as I could. This is my seventh autumn season in the region, but I still haven’t gotten a shot of the side of a mountain covered in rich yellows, oranges, and reds. Well, there was nothing to do but head upstate into the forests and hope for the best.

Of course, there’s nothing simple about changing leaves! There’s lots of interesting biology that goes into turning and shedding leaves (see MinuteEarth on deciduous trees and changing leaf colors), but we’re talking about the brain here, and there’s certainly nothing simple appreciating those colors either. Back to BAM!

The visual system

Ahh, neuroanatomy. When an artist draws a human brain, it’s usually just a big gelatinous blob with a few squiggles. That’s definitely how I saw it, anyway. Well, turns out that each sulcus and gyrus handles pretty specific processes, and the patterns are conserved between all humans. And the connections between them and all the inner brain structures?! For instance, to see the vibrant autumn colors, my eyes send signals through the optic nerve, optic chiasm (sometimes), optic tract, lateral geniculate body, optic radiations, and eventually to Brodmann’s area 17 in the occipital lobe in a retinotopic organization around the calcarine fissure. bla bla bla

Umm.

Needless to say, I’m relieved to have finished neuroanatomy this week. I can do without hearing the phrase “bitemporal hemianopsia” for a while.

Storm King Art Center

By the way, all these sculptures are from the Storm King Art Center, about 60 miles north of NYC and accessible by NJ Transit. It’s a humongous outdoor sculpture garden nestled into the trees and rolling hills. There are some themed permanent installations, notably the matching orange steel behemoths that tower 40 feet over airy lawns. Pieces like the three-limbed inverted Buddha sculpture and the mirror fence are gaining a reputation too. Provided it’s not closed for winter, you could (and should) easily spend 4 hours there.

However, what drew me there was that its expansiveness meant that I would be among people (therefore safe) but I would also have the space and time to think.

Auditory processing

What’s funny is that I can’t get away from BAM even when engaging in my leisurely activities. Of course the brain takes care of sound perception too, and I’ve learned some cool facts about music and auditory processing. The cochlea, our sound-sensing organ, is a magnificent structure. Not only do you have something bad-ass called a bony labyrinth built into your head, you also have built-in microphone that amplifies or attenuates sounds, your ear self-generates sounds that doctors use to diagnose hearing loss in infants, and cochlear implants can restore hearing! Err, actually it’s more impressive that the brain can make heads or tails of the input of cochlear implants.

Still, as a musician, I’m most blown away by how most people’s brains manage to dump perfect pitch info yet retain relative pitch (here’s my old rant about that). Also, Minute Physics has a wonderful short video about piano tuning and pitch that all musicians should watch.

Other leisurely activities: reading. Umm, the condition of inability to read is called alexia, and my brain reads that word as a girl’s name (meta, right?). It’s also possible to be able to write but not read; patients like that can’t even read something they just wrote!

Autism

What I actually wanted to say about reading is that recently I reread Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (now a hit Broadway show), which actually has little to do with a dog and has more to do with a boy with autism.

The way I think of autism is this: social interaction is the highest level of function that the human brain has ever attained. It requires the integrating visual, auditory, and speech cues with memories, interpretations of emotional states, and complex understanding of social norms to produce real-time nuanced responses. Autism is what happens if a brain doesn’t get it quite right. Kids who have prototypical autism just don’t get it, where “it” is every single inscrutable rule that governs interpersonal relationships that are somehow effortlessly acquired by all other babies. (babies’ mental maturation is a miracle; see this TED Talk). Instead, their autistic brains become stuck on repeat, and they become disproportionately and obsessively fixated on random things. It’s like a record that skips back to the same two seconds of music ad infinitum and ad nauseum, and there’s nothing an autistic brain can do to unstick itself.

Probably every section and every pathway in the brain’s cortical network strives together to eventually achieving the vague unified function of social appropriateness, so it’s no wonder that scientists can’t find a single responsible gene or single environmental scapegoat (vaccines, I’m looking at you. So is Jimmy Kimmel). There are so many ways for social understanding to go wrong, and that’s why autism can be so varied. It rarely always manifests as dramatically or poetically as it does in Curious Incident or the movie “Rain Man.” In fact, in the DSM-V (the definitive book of psych disorders), it’s now known officially as autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

But if autism is a spectrum, who’s to say where the spectrum ends? And, well, where do I fall on it?

When I was 4-ish, I was brought in to be evaluated for autism. Reportedly, in preschool I did nothing but cry constantly for a couple years. That’s a frightening prospect that definitely fulfills the criterion for social impairment. The second diagnostic criterion of ASD is becoming disproportionately and obsessively fixated on random things… and that’s basically the story of my life, haha. Thankfully, my brain has intact infrastructure for having eventually learned better social interaction (at least I hope!), so I don’t think I have autism, but I wonder… what would have been like to grow up with the label “autistic?”

Speaking of labels, under DSM-V, Asperger Syndrome technically isn’t an official diagnosis anymore but instead is included under ASD. Individuals with Asperger’s used to favor having it called Asperger’s because “having autism” carried a certain negative connotation. On the flip side, kids diagnosed with autism get special government support in education (which works really well, by the way), so maybe the favoritism will reverse. Indeed, more and more children are given the label of ASD every year. However, that rise in autism diagnosis rates, does that represent more kids actually developing autism now or more kids who wouldn’t have been labeled such before being thrown under the label? And returning to my original musing about myself, what does that label mean for those kids?

I have no answer.

Personality

Speaking of more labels and more reading… I’ve been reading Quiet by Susan Cain, a book about introverts living todays extroversion-favoring society. Favoring extroverts — gregarious people who thrive in social situations — is just something that just happens mathematically in a social species. Throw a collection of many people into a social situation and by definition it’s extroverted individuals who thrive and garner the attention and admiration of everyone–introverts and and extroverts alike. In the situations where introverts thrive, such as private sessions where they can take the time to think and act deliberately, there’s just no one around to appreciate it. Sucks for us.

A couple ideas Cain mentions in the book: unfortunately, teaching towards extroversion is more cost-efficient, as bigger classes require fewer teachers. The business world rewards fast-thinking and charisma and connection-making ability much more than a capacity for focused concentration and thoroughness. According to some studies, the trait of introversion is roughly half genetic and inborn (as “high sensitivity” to stimuli), and a third to half of all people are more introverted than not. And most parents try to pound that introversion out of their kids.

As a very dramatically introverted guy, I appreciate all the work my parents did in training me how to compensate for my shyness, but my social anxiety is still punching me in the face. If I thought school bad because they threw bunches of similar people together for years at a time and expected them to connect, (pseudo-) adulthood is way worse. Now, professional networking events and cocktail parties and drunken bar sessions are the de facto methods for people to connect, and that sucks too.

Thankfully, it’s the digital age! The internet empowers introverts to plan messages, draft emails, and meet/impress others with precision, all without ever stepping into a social situation! The internet also helps tackle the introvert’s eternal struggle to unearth and meet other like-minded introverts (but that’s a topic for later, haha).

If you want to learn more about your personality type, I recommend the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator test. It subdivides people into 16 different categories which are broad enough to cover everyone but specific enough to resonate with people, and it’s quite popular.

Med school friends

Medical school selects for an interesting demographic: a hybrid between focused academic monsters and sociable and benevolent angels. We all know it, and it’s kinda great. One of our funniest BAM lectures was the one about personality disorders. Our psych unit leader prefaced it with “we’re talking about personality traits, and all of you have personality traits. and by the end of the session, about half of you will think that you have one of these disorders, and the other half will think the person next to you has them but you don’t, and everyone will end up with a disorder.” And it’s true! Most of us probably have a touch of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (we’re neurotic med students, after all), and maybe a bit of narcissistic save-all kind of personality disorder.

Humor aside, I really like my classmates. Cornell keeps our class small at 101 (<Dunbar’s number), which means we attend small group, study, celebrate, and commiserate together. And we’re almost halfway through this strange journey called med school already, and that’s crazy.

Optho and family

I got to learn about my family history because BAM also covers ophthalmology (why is eye medicine so hard to spell? gosh). Myopia — nearsightedness — runs rampant in my family, so I had regular checkups while growing up to manage my predictably failing vision. In fact, those appointments are my most clear (lolpun) memory of pleasant interactions the healthcare system, so thanks, eyes!

My atrocious vision would have been selected out in some prehistoric context when I failed to see a sabertooth tiger two feet in front my face, but my privilege of growing up in middle-class America turns myopia into a minor inconvenience. In fact, bad vision is a separated into the whole different field of optometry, and other doctors don’t even mention it because it’s such a stable and “harmless” condition. Certainly, I don’t consider it as core part of my identity. It’s just my eyes, whatever.

Creating psych illness

The privilege of a stable middle-class home environment also means that I was raised by the most supportive parents anyone could ever hope for, and that brings us straight back to psych illnesses. It raises the most poignant lesson that BAM has taught me: Psychiatric illness can be created.

Yes, created. Not induced or triggered, created. Many of the psychiatric patients I’ve met have come from households rampant with substance abuse, alcohol abuse, physical and emotional abuse. Being born into a bad family wasn’t their fault, was it? You can’t blame all those young college girls for getting cornered and raped either. Men and women get sent to war so they can personally bear the responsibility of committing horrible deeds on behalf of an entire country.

What illness are created? How about anorexia nervosa, the eating disorder? No one can disagree that unrealistic beauty standards and societal pressures are contributing to skyrocketing rates of anorexia nervosa in young impressionable girls. Additionally, I was surprised to learn how deadly it is as a disease, as being that malnourished is acutely physically dangerous. Disturbingly high rates aside, it is nightmarish to watch a person to diminish in size and health and control as they physically waste away. We were shown this clip of Oprah reflecting on Rudine, and it’s just… viscerally troubling.

What else? Think post-traumatic stress disorder. At Westchester, I met a bright, strong, and selfless man whose mind and body have been ravaged by PTSD and subsequent alcohol abuse. He wasn’t bullied in school, but that’s because he learned to fight them off with all the practice he had protecting himself and his little sister from his abusive mother. He carried that skill through his military and correctional career, but I never learned exactly what happened then, because when he tried to talk about his military experience, he transformed instantly from an articulate and intelligent gentleman to a stuttering, fidgeting, hyperventilating, nervous wreck. It was scary. Combine that with the fact that he’s 50-ish and already confined to crutches/wheelchairs because he’s legs can’t support his weight, but still lives alone except when he has to take care of his mother (yes, the one that abused him), I can’t help but feel sorry.

And scared. There is no such thing as immunity to psychiatric illness. Just look at depression.

All I will write for now is that antidepressants work and no one should attempt to wage a war on depression alone.

We don’t understand

Let’s compare organs really quick. The heart’s an important, but we have a fairly good idea of how it works and how to treat lots of its diseases. Yeah sure, we praise it for being such a hard-working engine that can never sleep, okay. But think of it this way: the brain is the only organ that needs to sleep. What.

We understand so little about the brain and all its complex glory. At Cornell, we’re currently taught about microglia — one of the four brain-exclusive cell types — through new scientific journal articles because there’s so little established knowledge about them. And yeah, neurons use neurotransmitters with familiar names like dopamine and serotonin, but think of it this way: the brain accomplishes everything humankind has ever achieved — the industrial revolution, Beethoven symphonies, general relativity, love — by passing around a few molecules and electrical signals between neurons. Wut.

It blows my mind how limited we are in treating psych disorders with drugs, but it especially blows my mind that the drugs work at all. Take antidepressants as an example. We eat this stuff called SSRIs that messes up serotonin signaling, let it lodge itself in the brain, and hope it helps depression by improving one of our highest human functions (mood) without affecting anything else in the brain. It’s like trying to change your car engine oil by throwing a barrel of petroleum at it. It’s like trying to fix your computer by zapping it with a bolt of lightning. It’s like gluing fourteen gloves onto each of your wrists to have more fingers and expecting them to help you write better essays. But somehow SSRIs work?! WTF.

The disconnect

The disconnect between an autistic child and the rest of society. The disconnect between the eye and the brain in retinal detachment (my worst visual nightmare). The disconnect between mind and reality in schizophrenia, the disconnect between body and perception in eating disorders, the disconnect between malicious actions and remorse in psychopaths. That word can mean so many things, and there’s more.

A disconnect can mean naivete, especially in youth. I used to think that brainstem tumors were not nearly as dangerous masses in the brain itself. I mean, the brain’s that big and the brainstem’s that small and just holds up the brain! Well, after spending one week studying cranium anatomy and a whopping six weeks on brainstem anatomy, I realize that’s totally backwards. The brainstem transmits every connection from the brain to the rest of the body, all it’s concentrated in that cramped region. Brainstem lesions can be really complicated too. Now I know why a mass in the brainstem compressing cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII can lead to hoarseness, shoulder muscle weakness, and unilateral tongue atrophy.

A disconnect can be between doctor and patient. Thanks to a handful of hypochondriacs, doctors have to be suspicious of all their patients blowing their symptoms out of proportions. You can imagine if a guy comes into a general practitioner’s office complaining of a weird-feeling throat and saying “something is wrong,” the doctor might just prescribe him cough drops and send him home. Maybe the second doctor might be inclined to also dismiss his throat complaints and so-called weak shoulder and send him home with cough drops and a gym pass. Or maybe the third doctor might actually believe the patient when he insists that something is wrong. Maybe doing a full cranial nerve exam (like we’re being taught this week) may reveal that the patient is unable to move his tongue to the side anymore. Maybe then the doctors should start listening to what the patient had been saying all along: “something is wrong.”

Our neuro unit leader has this motto: “the patient is telling you what’s wrong with them.” It may take a bit of decoding of casual terminology and encoding into medical jargon, but patients live with their bodies day in and day out, so they know it best. I’m starting to believe that mentality, but I have a few reservations. What if a psych disorder causes hallucinations or illusions? Or… what if your patient can’t tell you anything?

There’s a condition called global aphasia that renders a person completely unable to understand or produce any language, and it can happen when a person suffers from a left middle cerebral artery stroke.

The MCA

It’s a familiar but nightmarish story: an older woman with a history of heart problems suddenly falls down with no warning, as if her right leg was just switched off. She tries to right herself, but something’s switched off her right arm too. Her husband rushes in to help and rolls her up to sit and asks her what happened, but he is horrified. Her right face seems as if it’s melting straight off her skull. She looks back at him crookedly with one eye, but it looks as if she can’t understand a word he’s saying. All she can do to respond is loll her mouth open sideways.

The left middle cerebral artery (MCA) feeds the areas of the brain which control language comprehension, language expression, and basically the entire right side of the body. Because it’s such an enormous artery, a stroke that blocks its blood flow will have an enormous “ischemic core,” the central area where the neurons die completely. Even if the woman is rushed to the hospital and the neurosurgeons dive in and fish out the clot, there’s no saving that region. A left MCA stroke is one of the most severe strokes that can leaves the person alive/non-comatose to suffer the deficits.

Sadly, the MCA is also the most common stroke location. This week, when we had our practice sessions for the neuro exam (reflexes, muscle strength/coordination, sensory tests), many of us saw patients who had suffered left MCA strokes. Even two weeks after the “cerebrovascular accident,” they still couldn’t understand anything. We also visited the physical rehab unit, where we found out that relearning how to walk — even with months of daily therapy — is considered a miraculous recovery. Also, because of the disproportionate representation in the brain of the delicate hand, none of them will ever regain any semblance of dexterity. Basically, the prognosis for an MCA stroke: suffer and then die.

That’s where one last disconnect comes in. The necessary one between doctor and patient.

As a med student, a budding clinicians dutifully trying to learn the neuro exam, you walk into a room and ask the patient if it’s okay to practice on them. The family gives you tentative permission while the baffled patient who doesn’t understand a word of anything stares blankly back at you. Then you do stuff like shine lights in her eyes and rub her arms funny and attempt to direct her with gestures to do crazy stuff like repeatedly touching her nose then your hand with her finger. Now, the patient’s confused and afraid and the patient’s family is freaking out about your experimentation and trying to shoo you away. And then you, as a med students trying to prove yourself, go to the faculty and report using stoic words: “unable to complete neuro exam because of global aphasia.”

Or say you’re visiting a radiology reading room and the resident gestures you to come see this striking MRI of a left MCA stroke. A brain is supposed to be symmetric, and this one’s definitely not. The resident starts dictating his report with rehearsed and bored phrases like “massive hyperintense hemorrhage in left hemisphere” and “significant mass effect with deviation to the right.” When he’s done recording, he closes the scan and says offhandedly “yeah, she’s never gonna recover from this stroke.”

Or say you’re a young intern on your neuro rotation and you’ve just finished a long shift full of migraines, back pains, dizziness, a couple seizures, a spinal cord injury from a car accident, a huge glioblastoma, and other terrible brain lesions. But one patient stands out in your Mind and sits heavily in your Brain. You sneak quietly back into her room, kneel by her bedside, and hold her dead hand gently in your hand. The room is dark, with only with the glow of fluorescent light filtering in from the door and only the sound of the mechanical beeping of heart monitors beating from outside. Her fingers curl slowly and stiffly in response to your touch, and her left eye gazes crookedly and blankly yet urgently at you. You meet her eyes for a moment. Even though you know she won’t understand it, you whisper to her a simple but heartfelt phrase: “I’m sorry.”

Then you have to pry your hand out of hers, walk out of the hospital, go to bed, get ready for the next long shift, and disconnect your thoughts from this next stroke victim.

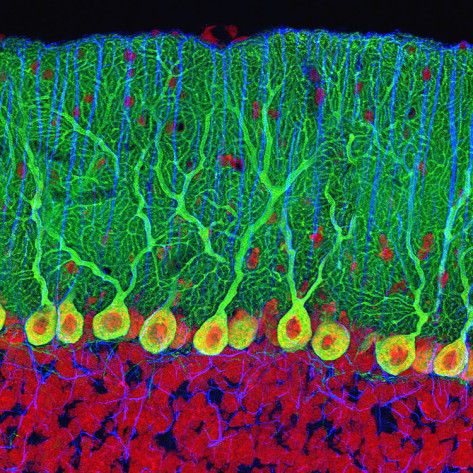

Purkinje nerve cells in the cerebellum.

I’m not quite sure what point I was trying to make by writing all this, but let me conclude with trees.

Trees

Forests have always been my favorite natural environment, especially the redwood groves and the mixed pine mountains that my parents showed me when growing up in California. There’s something about them — the trees there — that makes them so steadfast and magnificent and beautiful.

On the other hand, these deciduous forests here in New York and the northeast are wily and dynamic and beautiful in a different way. It feels strange to anthropomorphize our trees (they don’t have brains, after all), but the four seasons here make me wonder if they’re trying to wave their arms once every year to catch our attention.

But after BAM, I now have this new “intrusive thought.” That is, there’s a part of my brain that screams “NEURONS” every time I see a grove of trees. They just look structurally alike! Especially Purkinje nerve cells, which have their cell bodies and single long and thick axons (tree trunks) arranged perpendicular fashion and have the input from this complicated web of dendrites (branches and leaves) held up by those axons. The signals travel down into the layer below (roots) and make connections to more and more things in the deep ganglia underneath (earth). With a little stretch of imagination — which is also a job for your mind — wandering into a forest of trees can feel just like diving into a brain of grand proportions.

Here, there are ideas to find.

(topics I wanted to cover but didn’t have a chance to weave in)

- The Mental Status Exam, its oddity and its diagnostic value

- Depression and social stigma

- Alzheimer’s, the feared demon of old age

- EEGs and epilepsy

- motor learning, basal ganglia, muscle memory