A very New York thing happened today: my friend won a lottery for front-row seats for the Tony-winning Broadway show “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time.” The play was brilliant, and I enjoyed myself thoroughly with laughs, gasps, and tears. But wait, there’s more!

For those of you don’t know, “Curious Incident” is indeed a murder mystery (this post avoids spoilers), but it also revolves around the world and maturation of 15-year-old Christopher Boone, a boy with mathematical talent and severe social difficulties characteristic of autism. What a coincidence that I get a ticket during my psychiatry clerkship at NYP Westchester. Next week I’m visiting the Center for Autism and the Developing Brain to observe treatment, meet the director and psychologists, and start planning my next year’s research project in clinical autism. So yeah, I’m non-trivially interested in autism. Also, Mark Haddon’s 2003 novel — on which the play is based — is one of my favorite books.

But first, let me rave about the Broadway production!

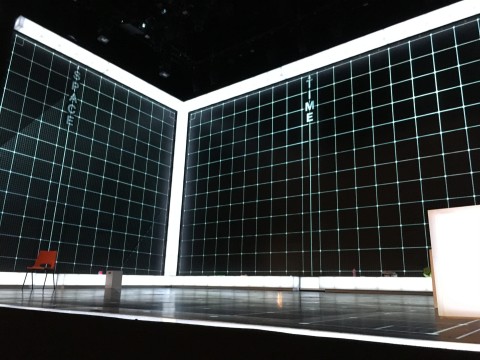

The staging was brilliant, literally. The three walls and the floor were a grid of lively LEDs and projectors cleverly used throughout the production. The stage’s frame comes alight too, and there are many platforms and cupboards and unexpected sliding walls that bring the stage to life. The staging represents the rigid mathematical perception of the world in Christopher’s eyes. For instance, even when we are told he is on a grassy knoll, the stage remains a strict 3D grid and only changes by glowing green.

As always, Broadway knows how to tell a good story, but the interpretation is especially important in “Curious Incident.” Much of the dramatic tension comes from Christopher’s unusual perception and broken interaction with other people, which is only hinted at in the novel (which is written as a first-person narrative) but must be flushed out on stage. When Christopher snoops around the house, he shines his torch directly into the audience’s eyes. They communicate the chaos of crowds with an ensemble walking in brisk constant-velocity straight lines at right angles with Christopher shrinking in the other direction, shirking from interaction, and shrieking in panic. They depict his sensory overload artfully with the wall projections, strobe lights, and dramatic cuts. And the sequence of Christopher imagining the life as an astronaut (for the most innocently endearing reasons) was masterful. My favorite moment.

And wow, the role of Christopher. Today, we saw Ben Wheelwright portray our protagonist. It is a role where every detail — the crook of his tensed left hand, his neck wrenching to the side when he plays with his toys, the agitated avoidance of eye contact, the intensely painful rocking, moaning, and groaning — must satisfy the audience’s preconceptions of mental illness in a politically correct manner. From our front-row vantage we could see beads of sweat pouring down his brow from the exertion of his exceptionally physical part. Christopher is essentially onstage continuously for 2.5 hours drawing huge chalk diagrams, and running off the walls, and doing flips and stuff. I have to say though, for a 15-year-old who supposedly subsists on strawberry milkshakes and spends hours curled up in closets, Wheelwright is way too fit (twice he’s shirtless and dammnnnn).

Now that I’m more familiar with psychiatry and mental illness, I’m even more impressed by Haddon’s writing. He wrote the book without being an autism expert, yet many experts praise his depiction as accurate and insightful. Christopher’s traits — his struggle with the nuances of language and nonverbal communication, his restricted interests and strict rituals, his enuresis (bed wetting), his tantrums when touched or overloaded, even his savant-like mathematical talent — are idealized autism but still realistic.

Likewise, Simon Stephen’s interpretation and Marian Elliott’s direction are essential for the stage adaptation. After all, autism is the condition of impaired interpersonal communication, and the audience must see how the world struggles to connect with Christopher. In the book, Christopher is rarely aware of the rifts that he tears between people; on stage, we watch conflicts unfold explicitly. His dad is hot-headed and struggles earnestly to raise Christopher from day to day. Siobhan, his special education teacher, knows how to connect in Christopher’s unique way and helps him make sense of things. Meanwhile, the rest of the world encounters Christopher with bewildered exasperation; they make sure he’s out of immediate danger but then back away slowly.

Of course, “Curious Incident” is a poetic Broadway-friendly interpretation of how we think a moderately autistic and mathematical mind might see the world. As medical student familiar with autism, I had a front row seat to this show, and it was awesome. But really, we’re just spectators and speculators. We infer their inner workings from how we observe them interacting with the external world, and we conjure up an “artistic rendition” of the insides of their heads. The very nature of the disorder makes the autistic brain tantalizingly inaccessible and thus fascinating and beautiful.

If you’re in NYC, go see the show before it closes in September. No matter where you live, you should read the book.

(sources of images: curiousonbroadway.com and amazon.com)