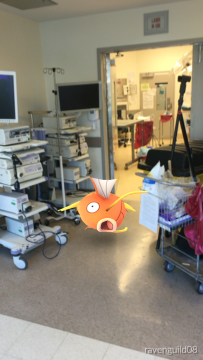

For the past month, I have mostly played Pokémon GO standing still in the same place: in the operating room hallway during spare minutes between surgeries while I wait for patients to arrive. The ORs are right on the East River, which means all day (and I mean all day) I only get to catch water Pokémon, mostly Magikarps that are flopping around. This is pretty ironic on many levels, but it also got me thinking.

This is not the way that Pokémon GO is supposed to be played! The game encourages real-life exploration with its Pokéstops anchored to actual landmarks scattered around cities and Pokémon that spawn in regional distribution. Heck, “go” is in the game’s name! We are supposed to run amuck to find the Pokémon, not be stuck at our workplace and intermittently boot up the game. Alas, there’s only so much I could do this month; this endocrine surgery service has an absurd schedule where I average 5:30 am-9:30 pm. That means there’s plenty of time to catch Magikarps and little time to do much else.

That being said, Several times I’ve found the time to run my phone through Central Park (i.e. look at my phone while running), and the density of lured Pokéstops is ridiculous. It’s commonplace to find a couple thousand players on the corner of 59th St and 5th Ave. Really, thousands. Like it’s hard to move around because there are so many people wandering around blindly while swiping at their phones. I am aware of how successful the app has been in moving the world. I’ve read news reports about players worldwide running into poles, into each other, across freeways, off cliffs, and I totally believe them. Pokémon GO is an engrossing game.

I consider Pokémon GO the first successful implementation of augmented reality, and just consider how much technology it requires. To have a Pokémon actually look like it’s in the world takes a high-definition real-time video camera synced with a precise 3D accelerometer. To have the Pokéball bounce on the top of an apparent surface takes decent image processing and object recognition. That’s not to mention the necessity for ubiquitous smartphones with amazing processing power and long battery lives, widespread robust cellular data, widespread GPS tracking, and a monstrous Google server system. Pokémon GO in its present state celebrates our modern mobile technology in its fullest.

Then, consider how much emotional drive it required to disseminate augmented reality to the masses: Niantic summoned power of nostalgia. Many of the Pokémon GO players are of my generation, kids who grew up alongside first-gen Pokémon, kids who played the games, watched the show, collected the cards, sang the song. Now in 2016, we find ourselves reenacting the exploring at catching-’em-all mentality that our avatars were doing two decades ago.

Pokémon was one of the biggest cultural phenomena of the late 90s, so influential that it also drove forward the technology of handheld gaming then too. Pokémon Red and Blue (and Yellow, I guess) popularized the GameBoy, the first handheld gaming system for the masses. The screen was kinda pixelated and monochromatic, but it ran for a few hours on 4 AA batteries, played music, beeped when we pressed buttons, and drew us into the beautifully imagined world of Pokémon. We lost ourselves for hundreds of hours in that world, walking around in that long grass and battling countless Rattatas and Pidgeys to train our team, or trying to dodge Zubats in caves and — of course — fishing up those darned Magikarps in the water.

I bet you that in the 90s, GameBoys and Pokémon inevitably found their ways into the pockets (Pocket Monsters, anyone?) of the OR staff of that time. Well, maybe. Pokémon GO on the ubiquitous multipurpose smartphone is easier to hide than a GameBoy amongst hospital beepers. How awesome would that have been though? I can totally imagine a med student in the Cornell University Medical College Class of 1998 standing in the very same OR hallway clutching his GameBoy and throwing his fishing line into the water off Cinnabar Island.

Meanwhile, the past two decades have seen leaps and bounds in medical and surgical technology. Take cholecystectomies as an example. Cutting out someone’s gallbladder for symptomatic gallstones has been the standard of care since the 1880s. For a century, a characteristic diagonal 4-inch scar in the right upper abdomen reminded them of their cholecystectomy. Then, in 1987, laparoscopic technology matured enough to let surgeons safely peer into an inflated abdomen with a camera, reach in with long instruments, and cut out a gallbladder. The laparoscopic cholecystectomy, or “lap chole” was cheaper, cosmetically less scarring, had less pain and shorter hospital stays and faster recoveries post-op. Within 5 years, open choles were rare in hospitals that had laparoscopic capability. Today, they’re pushing it even further with single incision (as opposed to four incisions) lap choles.

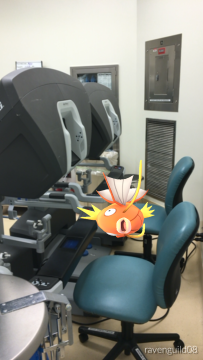

Then big med tech did what it does best: create all sorts of toys. In a single liver surgery last week, I saw — in addition to the standard laparoscopic fiber optic camera system — the Cusa ultrasonic tissue ablation system, LigaSure electrocautery vessel sealing instrument, Laparoscopic articulated ultrasounds, and Argon plasma coagulation (literally a blowtorch) all being used at once. It wasn’t even a robotic case! For those, we drive in an 8-foot ivory tower armed with four long menacing arms of interchangeable instruments. (Funnily enough, doctors still use beepers, but that’s a discussion for another day.)

All this advancement is marvelous, but it tethers us to our technologies. Most surgeons of this generation don’t even know how to perform open choles. Robotic cases are nifty, but it roughly doubles the base cost of any non-robotic version of a surgery, and it adds about an hour to set up and dock the robot. Technology literally tethers us too; in that liver case, the plethora of instruments turned into a mass of cables that got so tangled we had to pause untangle or to replace instruments that dropped.

Speaking of which, a surgery in which I get to drive the laparoscope camera is more than I am permitted to do in an average surgery. As the med student on the team, I just act as the mostly irrelevant second scrub on cases all day. In open surgeries, I help retract tissue so the surgeon and assistant can operate with a clear view and both hands. In laparoscopic cases, I usually stand around and watch because the technology enables the surgeon to do more for himself and blocks out everyone else. He is operating in a closed abdomen after all. Occasionally I’ll pass robotic arm instruments. When I’m scrubbed in, I’m sterile and can’t touch anything or turn around much, so I can’t study (I can’t play Pokémon GO either). And I’m scrubbed in for 7-12 hours a day. Yet, somehow at the end of my rotation, I’m supposed to have learned some surgery?

I mean, I love watching surgeries and I do so willingly and attentively. However, there’s no way that scrubbing in as the second, third, and sometimes even fifth assist is the most efficient way to spend my time learning. It feels inane. It feels like a misguided expectation that by scrubbing in to stand around for 8 weeks I am supposed to learn surgery.

These were thoughts I had in between cases, standing there in the OR hallway catching Magikarp after Magikarp. I told you it got me thinking.

You might know that Magikarp is the trope of inanity in the world of Pokémon. Magikarp has some of the lowest stats in the universe, knows only the useless attack “Splash,” and can’t learn other tricks. Magikarp’s sarcastic Pokédex entry: “Magikarp is a pathetic excuse for a Pokémon that is only capable of flopping and splashing.” Pokémon GO plays along with the meme. It takes 400 credits — four times more than any other lineage in the game — to evolve a Magikarp. That means catching 100 Magikarp. Magikarp is meant to evoke this reaction: “damn it Magikarp, another Magikarp!”

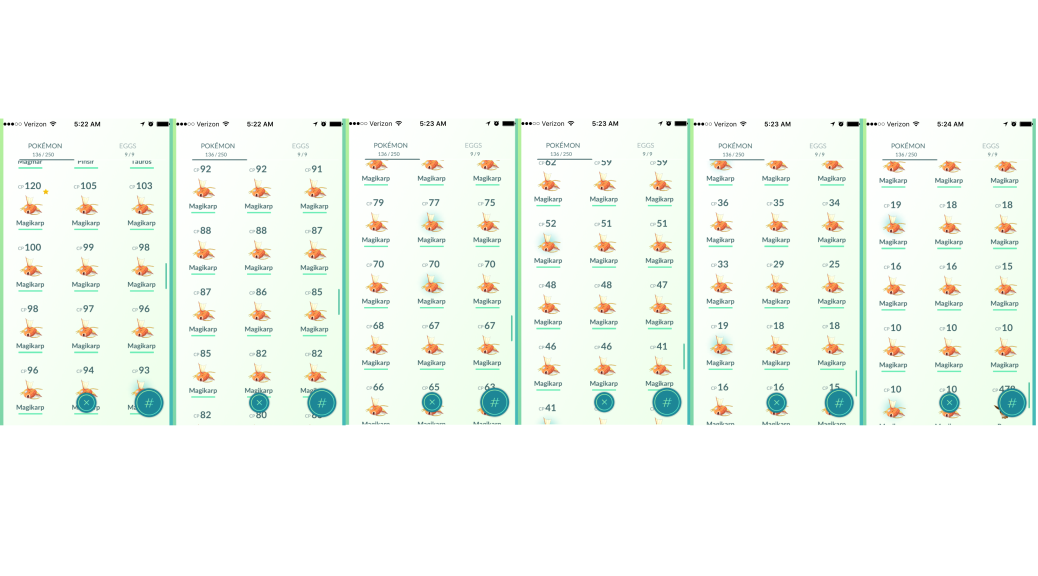

Catching Magikarp is boring and immediately ungratifying. Compared to say, Pinsir or Electabuzz or Bulbasaur — which are easy to find in Central Park — Magikarp feels inefficient, backwards, and masochistic. Yet, at a certain point, when I realized that being stuck in the OR hallway for 80 hours a week was garnering me many Magikarps, my mentality changed. I started seeking out Magikarps. I began booting my phone for a few seconds more often to nab a few more carps flopping around. I redirected a couple runs to follow rivers or pass by the Central Park bodies of water. At a certain point, I had more Magikarp than all other Pokémon combined (see screenshot above). All that for the monstrous flying sea serpent that is Gyarados, a worthy badge of my tenacity.

I have one more week left on surgery, still with the same endocrine surgery team. I’ll dutifully scrub in for like 9 more thyroid cases, silently fetching the skin hooks and vein retractors and army-navy retractors at the right time, anticipating which structures they’re dissecting and moving retractors appropriately, tensing and cutting sutures at the right time, undraping patients and accompanying them out of the OR. While waiting for the subsequent patients — when I’m not catching more Magikarps –I’ll be studying frantically for Friday’s shelf exam, which covers much more than just thyroids.

Epilogue: while transferring my Magikarp for credit in an exhausted stupor, I accidentally evolved the wrong Magikarp, ending up with a pathetically weak-ass Gyarados and wasting my month’s dedicated fishing efforts. There must be symbolism in that too.