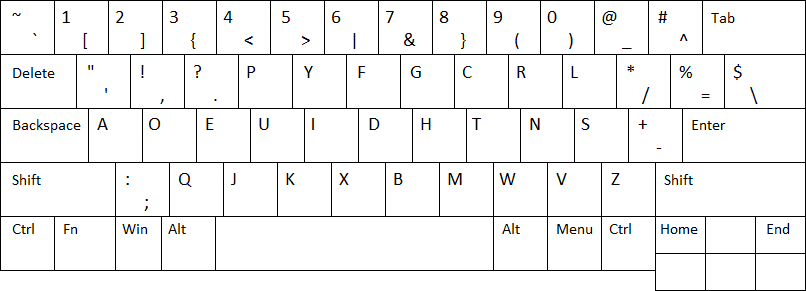

At home, I type in a strange custom keyboard layout that’s almost certainly unique (see above). The alphanumeric layout is Dvorak, but I’ve remapped most of the symbols and modifiers. Notably, CapsLock is Backspace, Backspace is Tab, Tab is Delete, and Delete was CapsLock. Punctuation is moved so ? and ! are with . and ,. Many changes are optimized for coding, such as moving brackets, braces, and the logical operands & and | to more accessible spots. I designed the layout in 2011 (and stopped coding in 2013, lol), but since then I’ve typed on it from memory on a normal Qwerty keyboard. I just finally bought a custom-printed keyboard to reflect my own layout, but not after strongly considering fully switching back to Qwerty. Let’s review the results of my protracted keyboard design experiment.

Check out My ‘Board

Okay but first, can we appreciate my sick custom keyboard!? I’m hardly a mechanical keyboard connoisseur and you’re probably not either, but c’mon, you’ve gotta appreciate this awesome 87-key from WASD Keyboards. There are two-tone alphanumeric keycaps for highlighting the Dvorak letter placement. There are maroon accent keycaps for my Bksp/Del/Caps/Tab remap. I made Windows keys be the radioactive symbol (perfect for radiology). The upper right Pause key is now a biohazard button, which toggles off my software-driven remaps so other people can type on it, except now you need to touch-type Qwerty because the legends are Dvorak! Ha!

The switches are Cherry MX Browns, but that was an afterthought. The board came fully assembled because I’m not about that soldering life, and it cost $170. No RGB backlighting, because I’m capable of typing in the dark (and also I’ve outgrown the taste of 8-year-olds). It’s a joy to type on, if not a little confusing; apparently I’ve mentally associated my wacky layout to the tactile feedback of my laptops’ shallow membrane keyboards.

Anyway. In retrospect, I regret switching to Dvorak. I do prefer the Dvorak typing experience to Qwerty because my hands remain in more comfortable configurations more often. (As a reminder, Qwerty has a messy history with a design that spaces out the most common letters towards the periphery, reducing the jamming of mechanical keyboards and/or spread out the load to multiple fingers.) Unfortunately, despite its design’s shortcomings, Qwerty is firmly established as the international standard for all digital alphabetical input, and — to no one’s surprise — it’s exceedingly difficult to deviate from that standard.

Qwerty Owns the World

Navigating the world with Dvorak in mind is difficult. It’s not just that my keyboard is completely unusable by anyone but me (though challenging my friends to try never gets old). I often have to use other computers, and every single one is in Qwerty. I still remember that in 2011, just months after making my remap, I disabled my layout to practice for the essay section of the MCAT.

It got worse when I started rotating and working in the hospital in 2016. Consider how we residents work: we hop between dispersed shared workstations in patient rooms, at nursing stations, in resident workrooms, or in clinic rooms. It got even worse when I started radiology where we dictate most of our text, eliminating most of my potential return on investment. And as much as I want to, I refrain from changing the keyboard layouts on hospital workstations because no one would be able to type and also no one would know why (though that’d be hilariously chaotic; IT would hate me [actually everyone would hate me]).

Even on my own computer, it’s a struggle with software. For instance, consider Adobe’s keyboard shortcuts for Photoshop, Illustrator, and InDesign, with shortcut maps balancing a combination of ease-of-access for the left hand and easy-to-remember labels, such as Z for zoom. Sucks for me, but Z in Dvorak is all the way to the right. Video games too; “WASD” is more elegant than “,AOE”, and all games seem to use Tab, which I’ve also moved to the right.

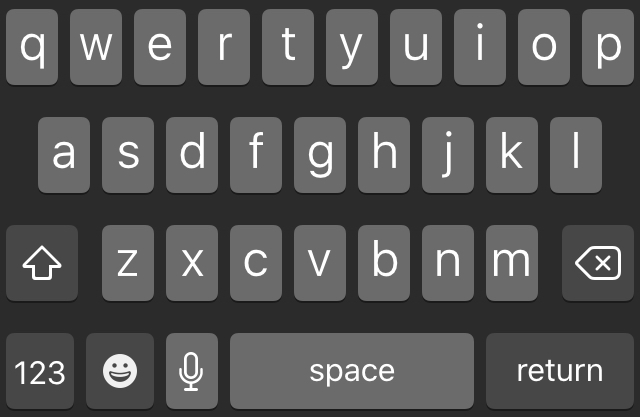

It’s not just computers! Kiosks driven by tablets are ubiquitous now (airport terminals, restaurant check-ins, the DMV) and they’re all Qwerty. Finally, I designed this before I had a smartphone, where two-thumbed typing on small interfaces is very much amenable to Qwerty…

How I Type Now

Now, in 2020, I text in Qwerty on my iPhone. I type in Qwerty at work. I switch my home computer to Qwerty for most of my Steam games. Custom Dvorak probably amounts to <5% of my text output (by time; by volume it’s probably <1% since dictating is so efficient). I can mentally switch seamlessly between the two layouts, but splitting my time between the two has probably made me slower on both. Measuring again now, I’m around 90 wpm in Dvorak and 95 wpm in Qwerty. I actually didn’t realize I’d become faster on Qwerty in the interim; apparently typing notes during intern year yielded some gains.

Looking back to the last post I wrote about Dvorak, looks like I already regretted switching in 2013, two years into the experiment. Still, the layout has been surprisingly durable, emerging largely intact over two laptops, Windows 8 and 10 upgrades, and a career pivot. The only changes were disabling my old “Shift-Lock” coding mode and adding media keys shortcuts for Spotify from F7-F9. Not bad, I’d say.

Happenstance Design, Lasting Ramifications

Now that I’ve invested in this physical keyboard, I think this layout is really cemented in my workflow for the long haul (Cherry switches are rated for 20-50 million keystrokes). I can’t rearrange these keycaps, as the symbols are printed with non-standard numbers, the keycap rows are contoured. Surely I didn’t think through all these consequences when I decided upon my key placements. The remapped symbols were placed with coding in mind, yet I hardly code now. In fact, I don’t even remember the coding languages that justified the placements! I was probably using Python and LaTeX, but yet that can’t be why I put $ alongside \. Is it because $ is an escape character in something?? Doesn’t matter anymore, I guess.

In that vein, Qwerty is like the ultimate compilation of serendipitous design choices culminating in a standardized design. Its original 1870s rectangular two-row alphabetical layout drew inspiration from piano keyboar, and a vestigial alphabetical arrangement lingers in the Qwerty home row. The 1/3 key-width leftward offset of the three alphabetical rows originates from the mechanism of typewriter hammers necessitating staggering, but lingers on most modern keyboards (except ortholinear boards). The names of keys — Shift, Return, Backspace — retain their names from how they physically executed their functions on typewriters. We’re so stuck with Qwerty mentally that smartphone keyboards use it too, even though dynamic touchscreens can use whatever input they please. It’ll be difficult to turn back on smartphones especially as the AutoCorrect dictionary and swipe keyboard patterns further cement Qwerty into the input paradigm for mobile devices.

Qwerty, an American invention, caters to the English alphabet and struggles with literally every alphabet (classic America). Even though there are international variations of the Qwerty layout, its tight spacing makes it tough to accommodate letter modifiers like accents, tildes, or diaereses, let alone additional letters. Check out the QWERTY Wikipedia page for diagrams of international variants, my favorite of which is the Icelandic layout which just unceremoniously shoves Þ, Ð, and Æ (thorn, eth, ash) on the right side.

Stepping even further back, the English language itself is a messy and confusing hodgepodge language, yet it has become the de-facto international language of the modern world. Because the modern world is digital (and pioneered by America), Qwerty has been inadvertently become the de-facto keyboard layout, for better or for worse. Therefore, anyone interested in navigating the digital world must learn Qwerty for its ubiquity.

In summary, having learned modified Dvorak kind of feels like being fluent in Pig Latin: a pitifully counterproductive parlor trick. Oh well, at least I have an icksay ustomkay eyboardkay!