As a radiologist, I have few clinical pearls to offer, but let’s talk about anatomical plurals!

This post all started when we were trying to discuss a fascinating case involving the male external reproductive organs, but we were all stumbling over the terms. So… one penis has a corpus spongiosum, two corpora cavernosa (each with a crus), a urethra, and a glans penis, but two penes contain two corpora spongiosa, four corpora cavernosa (four crura), two urethrae, and two glandes penium? And the corresponding scrota contain pairs of testes and epididymides, respectively susceptible to orchitides and epididymitides??

Penile jokes aside, let’s learn how to pluralize some anatomy! (Disclaimer: This is a humor piece; I have no linguistics training.)

To start with a gross oversimplification: Latin nouns have three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. This concept of gendered words is preserved in Romance languages; if you’ve learned Spanish, think la niña/las niñas, el niño/los niños. In English, we have a common borrowed Latin word, alumnus (graduate) with similar inflections. Take note:

| singular | plural | categorization |

| alumna | alumnae | feminine |

| alumnus | alumni | masculine or mixed/unspecified |

Consider this the prototype for the commonest inflection rules for feminine and masculine nouns. Along with the most common neuter ending of -um (think curriculum/curricula), we have the following pluralization guidelines:

- -a → -ae

- -us → -i

- -um → -a

This is great! This covered a huge swath of common anatomical terms. Some examples:

| singular | plural | etymology | notes |

| tibia | tibiae | flute | flutes were carved from such long bones |

| fibula | fibulae | brooch | named such because the two together look like a giant clasp |

| ala | alae | wing | the sacrum resembles a bat to me |

| calvaria | calvariae | skull | calvarium actually incorrect |

| aorta | aortae | strap | strap from which the heart hangs |

| cochlea | cochleae | snail, or its shell | |

| radius | radii | rod | explains why the geometric term shares a word |

| isthmus | isthmi | narrow passage | also used in geography |

| hippocampus | hippocampi | seahorse | hippo is horse, campos is sea monster |

| globus | globi | lump | lump in throat is perfectly named |

| focus | foci | focus | the pronunciation FOE-sigh irritates me |

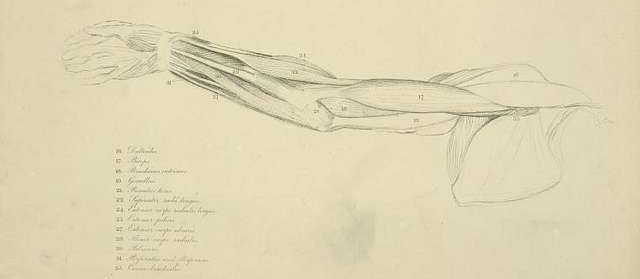

| brachium | brachia | arm | |

| atrium | atria | chamber | architectural term too |

| sacrum | sacra | sacrifice/vessel | see my old post about divination from sacral bones |

| dorsum | dorsa | back | lumbus was rarely used in English |

| hilum | hila | fissure |

It’s kind of confusing, isn’t it, how the plural inflection of the neuter -a can be confused with the singular inflection of feminine, -a? Unfortunately, there are way more overlapping inflections than these (I’m just going to gloss over Latin’s five declensions).

When learning Latin for a trimester in high school, as a modern English speaker, I found the construction of Ancient Latin so foreign. It’s not “article + subject + verb + preposition + adjective + object” but more like “noun with weird ending + noun with weirder ending + verb with weird ending.” Could it be because we study Ancient Latin with such reverence and mostly from refined, academic, nearly poetic documents that happened to be preserved? It all gives me a vibe of, like, trying to English from exclusively e. e. cummings poems.

Modern English is tough in its own ways, but mercifully pluralizing is simple. We don’t even inflect (that’s the term) our adjectives and adverbs.

- In English, to pluralize a noun, add -s or sometimes -es.

But English decided to preserve the pluralization rules for all these borrowed Latin words which are the foundation of medical English. I’m trying to memorize what I need using shortcuts and mnemonics.

For words ending in -x, I’ve always found it perfectly logical to finagle the -x into other consonants amenable to appending the usual English -es plural suffix. Think appendix/appendices or index/indices. They never felt Latin-like, but whatever, I rolled with it.

- -x → -ces most of the time

- -nx → -nges

- -yx → -yges

| singular | plural | etymology | notes |

| phalanx | phalanges | battalion | we usually have 56 phalanges. |

| meninx | meninges | membrane | leptomeninges = pia + arachnoid, pachymeninx = dura |

| salpinx | salpinges | trumpet | |

| syrinx | syringes, syrinxes | pipe | interesting how English corrupted the plural to syringe so now the plural of the anatomic term syrinx is often syrinxes for clarity |

| falx | falces | sickle | |

| appendix | appendices | hanging addition | appendixes was historically the anatomic term though |

| cervix | cervices | neck | most often referring to the uterine one |

| fornix | fornices | arch | C-shaped fiber tract |

Same with those words ending in -is that seemed to be pluralized by changing it to -es, once again kind of conforming to the usual pluralization in English where we accommodate for words that already end in -s with -ses. Coincidental resemblance once again, but whatever.

- -is → -es

| singular | plural | etymology | notes |

| pelvis | pelves | basin | extrarenal pelves is my most common usage |

| physis | physes | work of nature | truly miraculous, the growth of pediatric bones |

| naris | nares | nostril | I’m guilty of not using the synonymous modern word “nostril” |

| testis | testes | witness (to male virility) | think testament. This might be the most oddly specific derivation I’ve found |

| vermis | vermes | worm | you’ve got one on the back of your brain |

What surprised me is how quickly American modern medicine has turned its back on medical Latin. Ancient Latin and Greek were part of standard curricula at most universities and colleges until the late 20th century, and they were prerequisites for medical school until the 1960s or so. Now, Latin is very much not a premed requirement. Antiquated anatomical terms are of declining concern as they are eclipsed by an ever expanding corpus of new medical discoveries. I was taught anatomy in the 21st century by brilliant but exclusively foreign-trained surgeons. Pronunciation and classical grammar were… um, glossed over.

The first “irregular” plural that I really registered was foramen/foramina. Many others I had no idea I was missing. I was happily talking about corpuses (bodies), caputs (heads), scapulas (shoulders), genus (knees), and halluxes (big toes) failing to realize each one of those is incorrect.

Now we’re getting deep into the weeds of bizarre Latin plurals. These defy easy categorization for me, but I’ll try?

- ?? → -a (lol)

- -u → -ua

- -men → -mina (found two cases)

- -ns → ntes

| singular | plural | etymology | notes |

| os | ossa | bone | mostly I wonder how os is a word |

| femur | femora | leg bone | reminds me of ephemera. See my recent post. |

| foramen | foramina | opening | the OG weird plural I learned |

| putamen | putamina | shell | |

| caput | capita | head | per capita uses the plural accusative |

| occiput | occipita | against the head | |

| genu | genua | knee | genus is, of course, a separate singular |

| cornu | cornua | horn | like bicornuate uteri |

| pons | pontes | bridge | the neuronal pons is pretty pudgy for a bridge |

| dens | dentes | tooth | the odontoid process resembles one |

Here, I kind of got the sense that the plural tended to approximate the rules, trying to affix a terminal -a or -es to the root. It’s the singular forms which are modified root words. This particular group of nouns (3rd declension) seems to be a bucket with some of Latin’s most interesting words. Night is nox/noctes, death is mors/mortes.

If anyone was hoping to rely on quick and dirty pattern-matching, here’s where it utterly fails. Even though most Latin nouns that end with -us are the typical (2nd declension masculine) group, there are some which are most definitely not. Consider this family:

- -us → -i (most of the time)

- -us → -ora, -era, -ura

- -us → -us (plural is unchanged)

| singular | plural | etymology | notes |

| corpus | corpora | body | corpus spongiosum, corpora cavernosa |

| viscus | viscera | organ, usually bowel | perforated viscus, abdominal viscera |

| crus | crura | leg | diaphragmatic crura |

| genus | genera | birth/origin | used in genetics |

| ictus | ictus | blow/strike | strokes were broadly called apoplexy, “struck down by violence” |

| virus | N/A | poison | in ancient latin the concept of poison was uncountable, like how “music” is now. |

The most mind-blowing factoid I learned is that the plural of opus is opera. So like the opera house is where you go to listen to multiple works of music.

Returning to the words that end in -is, medical practitioners may be wondering about all who bunch of words that end in -is but do other crazy stuff with plurals. Well, they do different stuff because they’re Greek.

- -is → -ides (this is not generalizable, but handy)

- -itis → itides (consistent)

| singular | plural | etymology | notes |

| dermis | dermides | skin | |

| epididymis | epididymides | epi (upon) + didumos (testicle) | |

| epididymitis | epididymitides | inflammation of that thing | it’s so extra it cracks me up |

| hepatitis | hepatitides | liver inflammation | |

| glans | glandes | acorn | insert penis jokes here |

The -des ending appears prevalent in Greek-derived terms. Speaking of which, the plural of octopus is hotly debated. It’s Latin-ish, with the 2nd declension masculine ending, so maybe it should be octopi. However, it has Greek roots: octo- (eight) -pod (foot), so perhaps it should be octopodes (oc-TOE-poe-dees). Or maybe we should just be reasonable English speakers and call them octopuses. All three are accepted.

Many Greek inflections bear such close semblance to Latin inflections or were otherwise first co-opted by Latin and then borrowed into English that I haven’t bothered to try sorting out which came from where. Nonetheless, there’s one extremely common ending that must be mentioned: -on.

- -on → -a

| singular | plural | etymology | notes |

| phenomenon | phenomena | phainein is “to show” | |

| olecranon | olecrana | elbow head | |

| ganglion | ganglia | tumor near sinew | contrary to neuron |

| neuron | neurons | sinew | neura is not accepted anymore |

Modern medical lexicon (plural: lexica) has a funny collection of suffixes (plural: not suffices) that we love throwing onto the ends of words to describe pathologic phenomena. Specifically, -oma turns anything into a mass, -itis inflames it, -otomy puts a hole in it, -ectomy takes it out. Speaking of which,

- -oma → -omata/-omas

In proper Ancient Greek, I think the -omata is the proper plural, but it has been almost completely corrupted in modern medical English. The -oma ending is so ubiquitous and the -omata plural is so audibly antiquated, that we have collectively decided to abandon it.

| singular | plural | etymology | notes |

| carcinoma | carcinomas (carcinomata) | crab mass | tumor of epithelial origin |

| sarcoma | sarcomas(sarcomata) | flesh mass | tumor of connective tissue origin |

Medical understanding evolves quickly, as does the linguistics surrounding it. Novel terminology may be as simple as naming a novel coronavirus SARS-CoV2 after “Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.” There are other changes always happening too. Recently, we’ve been systematically abandoning eponymous diseases named after Nazi physicians. We’ve replaced terms like phthisis for tuberculosis, dropsy for edema (or oedema). But eschewing -omata is cool because it’s like medicine turning its back on Greek grammar itself. Now uttering granulomata or meningiomata makes you sound like a stodgy old dweeb. What a time.

Oh, but we are far from done. How about plurals of terms with modifiers? That opens a whole can o’ worms. Calix vermibus, if you prefer.

Latin has six cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, vocative, and ablative. We have been discussing exclusively the nominative case, the grammatical form where the noun is the “subject” of the clause. The genitive case approximates possessive, or the idea of “of the.” The other four I know basically nothing about. Each of the cases has a different inflection for the genitive case, and it’s different for plurals.

Oh yeah, remember how Spanish has two genders, and that’s about it? Latin has five declensions, which are kind of like superclasses under which gender can be a subtype. All those various endings listed fall into those subclasses, and you can take a look at the prototypical inflection tables for the five declensions and their subgroups, if you’d like.

We’re not done! Some anatomical terms are actually adjectives. In particular, some muscles take the form “[musculus] (adjective adjective),” where the word muscle is dropped in common usage. I haven’t bothered even looking at the Latin adjective inflection tables.

So a random collection of plurals involving modifiers, after which I completely gave up.

| singular | plural | etymology | notes |

| falx cerebri | falces cerebrorum | sickle of the brain | -i/-orum is 2nd declension male genitive |

| cavum septi pellucidi | cava septi pellucidi | hollow of the translucent wall | See this fun letter about cavum septum pellucidum |

| [musculus] teres minor | [musculi] teretes minores | lesser round muscle | adjectives |

| latissimus dorsi | latissimi dorsi | broad thing of back | lats is easier |

| quadriceps femoris | quadriceps femores | four heads of the leg | quads is easier |

| triceps brachii | triceps brachiorum | three heads of the arm | tris is easier |

| rectus abdominis | recti abdominis | straight thing of the abdomen | abs is way easier |

| psoas | psoai?? | psoa: loin (Gr) | apparently the French anatomist Riolan mistook psoas (genitive of the fem. psoa, nominative plural psoai) as a male nominative and established it in anatomy. I’m so done. |

I don’t mind, honestly. The corruption of classical plurals is hardly an affront to the giants of ancient medicine. Hippocrates, Galen, Vesalius, we honor them every day by practicing medicine built on the foundations of their discoveries. In fact, anachronistic devotion to obsolete terminology is self-defeating; why dictate a radiology report with correct Ancient Latin grammar if my colleagues can’t read it?

Language is awesome because we, as the speakers and listeners, collectively decide what is viable terminology. Our English rule of “if you want more then you should’ve put an -s on it” is so reliable. So, so many of the terms above have two recognized plurals. Femurs. Corpuses. Aortas. Pelvises. Penises. Scrotums. Regularity enables comprehension. That comprehensibility establishes their acceptability.

Disclaimer: To reiterate, this was written with casual research. The examples I listed should be correct, but the “rules” are but personal mnemonics.

Epilogue: Anyone play the New York Times daily minigame the Spelling Bee? They have never used the letter S, presumably because it trivially nearly doubles the number of valid nouns and present tense verbs.