Iceland. Land of Ice and Fire.

As a subarctic volcanic island, Iceland looks so unreal because its volcanic rock and black sand are contrasted by pristine snow and ice. Everywhere you turn, you can see where the geologically young island is being battered by water in many forms—the ocean, the glaciers, the waterfalls. Moreover, Iceland’s disturbing lack of trees makes it look even more alien. Instead, the land is studded with glaciers, moors, jagged cliffs, eroding mountains, and mossy lava fields.

Ever since I bought my camera five years ago, I dreamed of visiting Iceland myself. As I saw those glorious shots of sunlight filtering through ice littered on a black sand beach, I longed to take one of my own. I thought of pointing my camera at the night sky to capture streaks of otherworldly green and purple. Chasing waterfalls, climbing mountains, descending into cracks in the earth, I wanted to do it all.

Sadly, I had to wait for five years as I grew busier and poorer in medical school. Meanwhile, WOW air gained momentum, tourism in Iceland exploded with the Instagram age, and so many of my friends visited Iceland and beamed back their photos. I watched and waited jealously until, finally, I had my chance in March 2018, right before graduating. The hopes and dreams of a half decade, my entire photography career, all packed into a 12-day solo road trip around Iceland.

But in reality, could I have truly done justice to Iceland in two weeks? No. Confined to one season, working with only a handful of golden hours, and constrained by my own endurance, I had no chance of capturing in photos all that the island has to offer.

That’s okay though. Driving through Iceland was such an experience. Photos can’t tell you how a glacial tongue speaks to you in echoing dripping water or how it cuts at your boots with geometrically jagged ice. Mere photos can’t communicate the pain of leaning into howling winds, or the taste of crisp clear water straight from a glacial spring, or the feeling of standing in a vast valley of black sand. Maybe photos can hint at the awe of watching the aurora borealis from the comfort of a steamy geothermal spa, but—trust me—it’s better in person.

This is not a photo book of Iceland; I didn’t have the time or resources to stay and shoot long enough to make one. Still, I hope I’ve managed to capture some of the magical beauty of Iceland.

That’s the intro to the print photo book I assembled this week. I’ve always aspired to make my own coffee table-style photo book, and I’ve done it! The book is 100 pages long with and 175 photos from 80+ locations with captions. It’s quite expensive to print though, so I’ll see how it turns out when I get it in the mail… Here are a few excerpts.

For my series of inane elaborate selfies, see Instagram. They were super fun to take. For travel tips, see Iceland Tips. Or better yet, get in touch and I will happily rave about the island.

Svartifoss

4. Neither tall nor big, yet the “black waterfall” manages to be one of Iceland’s most striking waterfalls thanks to its menacing inverted-appearing basalt columns.

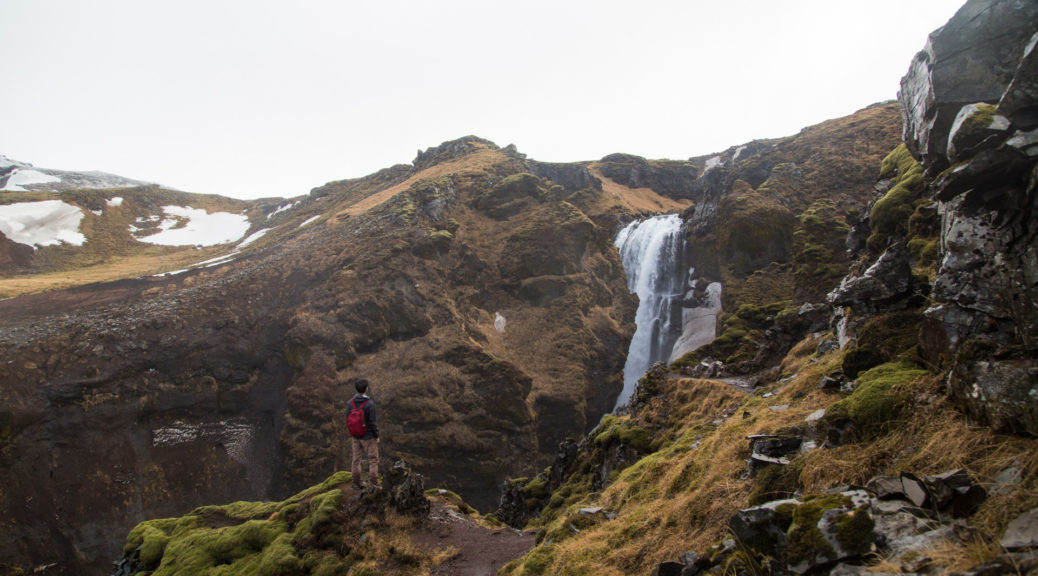

Glymur

5. Iceland’s tallest waterfall, at 198 meters, hides within a narrow canyon it has carved for itself. Its name means “tumult.” Well, it’s the tallest excluding a recently discovered remote cascade in the middle of Morsárjökull!

During the summer, there is a log bridge spanning the river so hikers can reach the east bank to see the waterfall. I had to ford the freezing river barefoot.

Dettifoss

6. Words and photographs cannot describe the frightening force of the muddy water that this “collapsing waterfall” pours forth. It is Europe’s most powerful waterfall.

Sólheimajökull

22. This glacial tongue of Mýrdaljökull, Iceland’s southernmost glacier, retreated a kilometer in the last decade, an absolutely blazing rate. Scientists estimate that with the current progression of global warming Iceland’s glaciers will all disappear within 150 years.

Kirkjufell

29. The “church mountain” off the north coast of Snæfellsnes is a picture-perfect example of glacial erosion. Its simple sloping contours look almost comical, as if Dr. Seuss drew the thing.

You can actually scramble up the side of the mountain. The first and last photos in this book are taken at sunrise from halfway up the east face.

Hverfell

38. This massive explosion crater dominates the landscape around Mývatn. I was lucky to see it neither all-black or all-white but rather with remnants of ice in the crags of the north face.

My attempt to hike the three-kilometer rim was memorable for the absolutely exhausting gale-force winds that threatened to sweep me off my feet.

Reynisdrangar

30. Off the coast of the village Vík í Mýrdal, Iceland’s southernmost point, loom these three massive 66-meter basalt stacks. Legend tells of two trolls trying to drag a three-masted ship to land but being turned to the stone pillars at daybreak.

Reynisfjara

31. The beach features a stunning variety of basalt rock formations: these photos were taken on sequential sections of the exposed cliff.

The surf is extremely strong here as the North Atlantic crashes in after being unblocked for hundreds of kilometers, and it has eaten away at the edge of the cliff Reynisfjall. It is the same surf that has carved out the basalt stacks Reynisdrangar.

Lóndrangar

44. On the coast of Snæfellsnes are these tall lava plugs, exposed when the pounding ocean eroded away the surrounding softer rock.

Hverir

50. This area near Mývatn is chock full of boiling mud pools, steam coming straight out of the mountain, and a strong sulphurous stench that the photos can’t even begin to describe. The smell of hydrogen sulfide is ubiquitous there; the taste even seeps into the hot tap water.

Borgarfjörður Eystri

58. Black sand beaches are everywhere in Iceland. Made from volcanic rock ground down by glaciers and the ocean, they look so wrong, like the world took a normal beach and inverted the colors and sprinkled on some ice.

This beach, on the northern tip of the Eastfjords, is the most remote place I managed to visit.

Mývatn

66. There’s a lot going on near the vast lake Mývatn. Parts of it were frozen, yet places just adjacent were steaming with geothermal activity.

Drangshlíð

67. Nestled under Eyjafjallajökull is a peculiar rock with cowsheds built into its caves. Legend tells of elves who helped birth calves at night but did not like interference.